Dear Saturated Readers,

I am writing to you, in part, from the living room floor of my dearest friend, Black feminist experimental filmmaker ariella tai—one of my favorite places to come home to in Portland, Oregon. However, it is with a heavy heart that I share with my Saturated community here on Substack that my partner, Mia Charnelle, lost their big brother on March 17, 2025, one year after a devastating week and month in March 2024, and a collective year of compounded and terrifying loss: their father Gregory L. Thomas, who raised them, passed away on March 2nd, just six days before their 33rd birthday; their cousin Linda on their birthday; their cousin Vonetta on the 9th; their cousin Jamarion on the 24th; a sweet friend of mine from college; my beloved close friend Cicely B. Rodgers who was also a friend of Mia’s in September; my family’s longtime family friend Evelyn Hyman, among other losses and a series of family health emergencies including some of our own—like my visit to the emergency room where I found out that I have diminished lung capacity and now asthma from long COVID.

After the painful year, we promised to at least try to create a new memory this March. One that would undeniably be shaped by immense loss and grief, but one that we could enhance with our personal styles, which we were excited to bring to fruition; moments that begged to be captured, along with the food we made room for in our bellies. As two people who are chronically ill and disabled, we pushed some of our boundaries and took a risk by traveling to Las Vegas—in celebration of Mia’s birthday, all that they had lost, and as our first vacation as partners in roughly six years, not tied to some beautiful obligation. Dear readers, can I tell you, we had the most precious time and created delightful memories that we hope will sustain us for many moons and sun revolutions to come.

Yet I am here to share (with permission and limits) about the compounding, complex, and layered grief that has since punctuated this vacation experience.

Upon returning to L.A. from Vegas, we were excited to rest and settle into our bed when, about ten minutes after arriving home, we received a devastating call about their older brother that compelled us to return to the airport right away—the very place we had just left— now heading back to confront another painful reality, one that has since resulted in the death of Mia’s older brother, Gregory L. Robinson, who had clear and exciting plans to show up in the world as a skilled jewler and underwater welder following his release from Deer Ridge Correctional Institute in Bend, Oregon. In December 2024, Greg had reported experiencing severe symptoms, including intense migraines, blurred and impaired vision, fluid buildup on the brain, lethargy, dizziness, and confusion, which had worsened significantly by January 2025 yet was met with alarming indifference to his pain and a refusal to provide adequate, meaningful, and timely, care by DRCI.

Needless to say, this has been one of the most devastating times in Mia’s life, as well as my own. Since Mia and I are partnered but not married, nor is our romantic relationship bound by the law at present, it has been its own kind of wreck to witness the cisheteronormativity that has barred me from this immense time of collective grief with condolences in the singular—underscoring how kinship that was severed by slavery and how attempts to form a family are undermined and gutted by the state and made visible by the everyday grammars we adopt and the silences we choose to invoke in the carceral afterlife of slavery (Spillers 1987, 75; Hartman 2007, 6; Haley 2016, 7).

I am keenly aware that, while I have been affected, I am not the most profoundly impacted person by the recent loss and its painful repercussions on our family. Nevertheless, it is the distinct, discrete, disjointed, isolated, and uncomplicated ways in which many of us have been instructed to comprehend and conceptualize grief that have intensified my focus on the collective and structural dimensions of this moment. The unintentional marginalization of my presence amidst the aforementioned grief and the subsequent expressions of condolence serve as a poignant reminder that the grief we experience is collective in this household and in our small community of loved ones- those few who genuinely care for and mourn with us. Furthermore, this period also serves as a critical reminder that we are not just mourning a singular death; we are mourning a litany of black loved ones that we have collectively lost since last year and throughout our lives, many of which were tragically abbreviated at tender ages due to “skewed life chances, limited access to health and education, premature death, incarceration, and impoverishment […']” (Hartman 2007, 6). Some of who we have lost include my mother, whom died during my pre-teen years (August 2002), my maternal grandmother who raised me following the loss of her child (December 2017), my father (September 2021), Mia’s paternal grandfather Howard Thomas Jr. (April 2000), and paternal great-grandfather Howard Thomas Sr. (May 2000); Mia’s twin uncles Dana (July 2001) and Desmond Robinson (December 2001); Mia’s maternal grandmother (2002), grandfather Willie D. Manning (2012), and Aunt Vivian Barr (2016).

We acknowledge that our collective losses, along with the numerous family deaths that Mia has faced between March 2024 and March 2025, are indeed devastating, but they are not merely a series of unfortunate circumstances. We are not unlucky; we are black. To view these deaths in isolation or as a sequence of disjointed misfortunes, rather than as compounded losses, is to structurally deny the succession of black death, or worse, to stage another black death through denial or abhorrence of the incapturable repetition. As a result, we are left with the horrifying question: What does it mean to grapple with the daily saturation of black death? This is to say, black death that is always present, even when the violence of singularity or narratives of misfortune obscure it.

Writing Death:

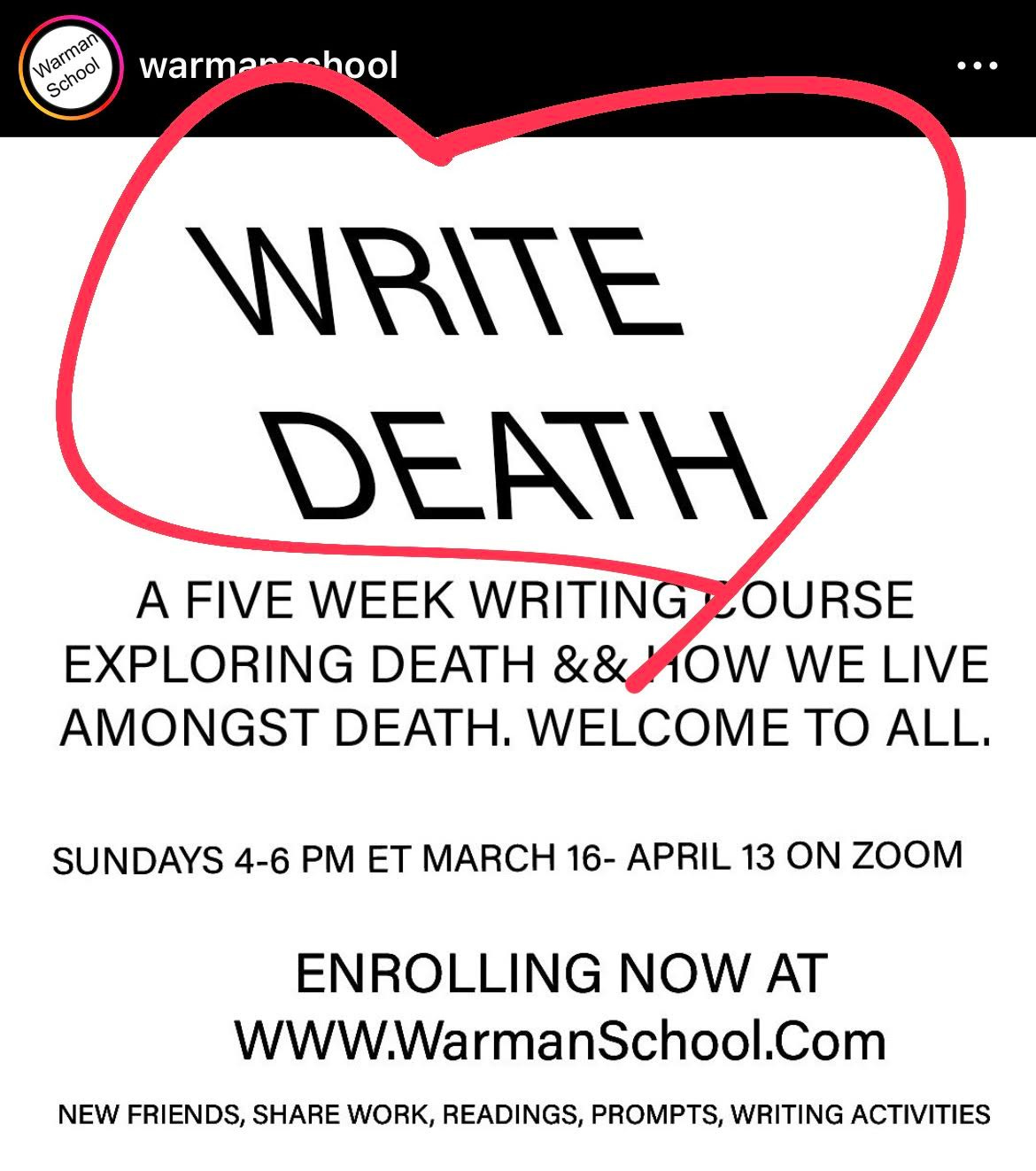

As a grief-stricken Scorpio, someone who has lost many core loved ones, and as a doctoral candidate whose work tarrys with the dark (black death), I continue to yearn for spaces with sustained time to think about death without the immediate intellectual and theoretical interruption about claims to a life that is not promised and can be abruptly taken from black people with no notice. The better part of me intuitively knew I would need a protected space like this, so the week leading up to our trip, I enrolled as a student in a five-week writing course entitled “Write Death,” taught by the brilliant and very fucking cool LA Warman at the New York City-based Warman School (which is not a school, hehe). This class has allowed me to grieve and contemplate death across multiple political registers in a cultural and political climate that so desperately (and understandably so) desires to unthink death—refuse it, sidestep, footnote, turn away from, and untether it from— ‘life’ though as if it were structurally given (to some of us) in the first place or possible in a world tethered and made over and over again by black death and its accompanying terrors.

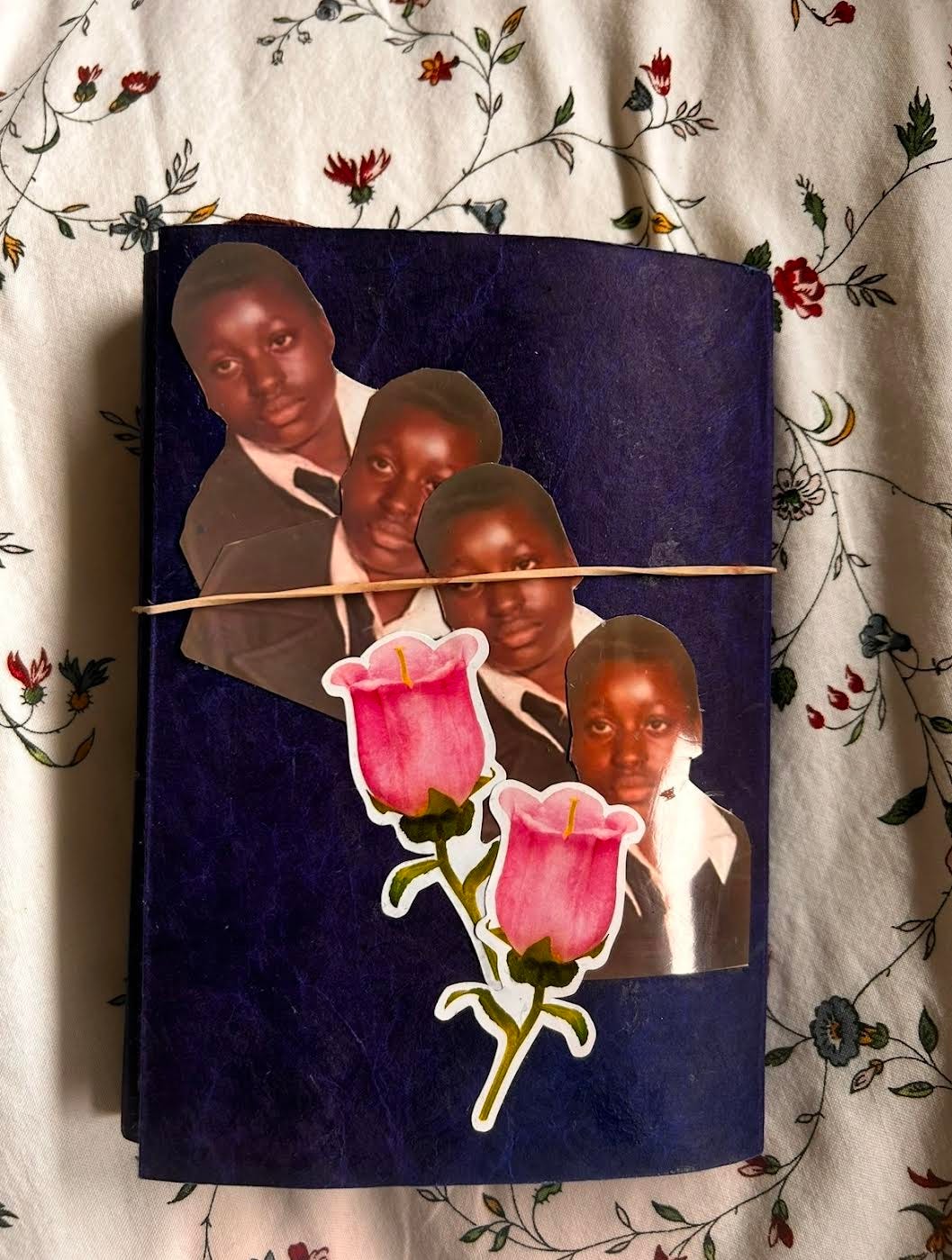

One way I have participated in Write Death is by reflecting on how death has shaped my youth and my present life, particularly given our recent losses. I engage with prompts offered in the class, such as: 1. What will you always be grieving? 2. How do you care for the part of you that is dying? 3. What prevents you from thinking about death? Through art, I have been able to explore the answers to these questions by starting my own junk journal focused on death and grief.

Morbid Rant, Morbid Death:

As a dark-skin, fat, chronically ill, and disabled person who has been characterized as leading a morbid existence and whose life has been reduced to “social dead weight”- a view reified and compounded by the BMI scale—it has been important for me to structurally attend to the entanglements between antifatness and antiblackness which largely remain underexamined in the mainstream and across many disciplines, in order to better understand the suffering of fat black people and black people who are deemed “inclined to be fat” (Strings 2019 & Oldham 2025). This class has been critical in extending my ongoing and forthcoming work (which will be in print soon *promise*) and in seeding new projects that regard ‘morbid’ as an index for a preceding antiblackness that is antifatness.

One question I have grappled with for *years* is the often-circulated sentiment that those (namely, Afropessimists, Black feminists) who think antiblackness as the or a structuring principle of the world/ing think antiblackness ‘too much’. Furthermore, the term itself at the level of grammar, application, and theoretical use and sophistication is too totalizing, too cumbersome, and, as black critical theorist Rebecca Wilcox has captured, we have been portrayed as loudly and imprecisely overstating its violence and are essentially death-obsessed. However, I have wondered about the viability and stakes of such a claim that purports that it is merely possible to discuss antiblackness in excess while the black fat body remains almost entirely underdiscussed (if not unthought) by most fields.

I am equally curious about mobilizing such a claim that extinguishes the fat black body from the realm of experiencing antiblack violence and forecloses an opportunity to think “antifatness as antiblackness” (Harrison 2021, 8). Moreover, I am wary about the implications of suggesting that antiblack violence can be counted or measured and how out of touch it might be to suggest or insinuate that black people living life as social death, including fat black people like myself, are death-obsessed when even at the level of grammar, black fat people are normatively fashioned in the U.S. as exceeding the capacity for life as (overweight) or as death (morbidly obese)?

More on this later. For now, I am still saddened by the fact that we are running out of space on our altar at home due to the many black people in our lives who have passed away.

Thank you for reading.

So Saturated (in grief),

Ebony Ro.

love and blessings to you 🕯️

Thank you for shating and writing this.